Reverse Polarity Protection for Your Circuit, Without the Diode Voltage Drop.

by ccrome in Circuits > Electronics

74961 Views, 26 Favorites, 0 Comments

Reverse Polarity Protection for Your Circuit, Without the Diode Voltage Drop.

Ever blow up a circuit because you reversed the polarity of a battery? Or got one of those pesky center-negative AC power bricks? Or even carefully connected your circuit to a bench supply, and still got the leads reversed?

Well, I have. It can ruin your day.

The easiest way to protect your system from a reversed battery is seen in the first image. Simply put a diode in one leg or the other of your circuit (usually the + side). If you don't care about your system's efficiency, and you have at least 0.7 V of margin when your DC supply is at its lowest possible value, then this will work fine. RLOAD represents whatever the heck you're running -- a microcontroller, a coffee warmer, whatever.

However, if you have less than 0.7V of margin in your system, you may replace the diode with a Schottky diode. This brings your drop down to 0.3V. Better, but still not great. For example, if you're running a system from 2 AA cells, you still can't afford the ~0.3V drop of a Schottky because you may have a chip that requires 2.0V to run, and NiMH cells bottom out at about 1.0V/cell.

So, what's a guy (or gal) to do?

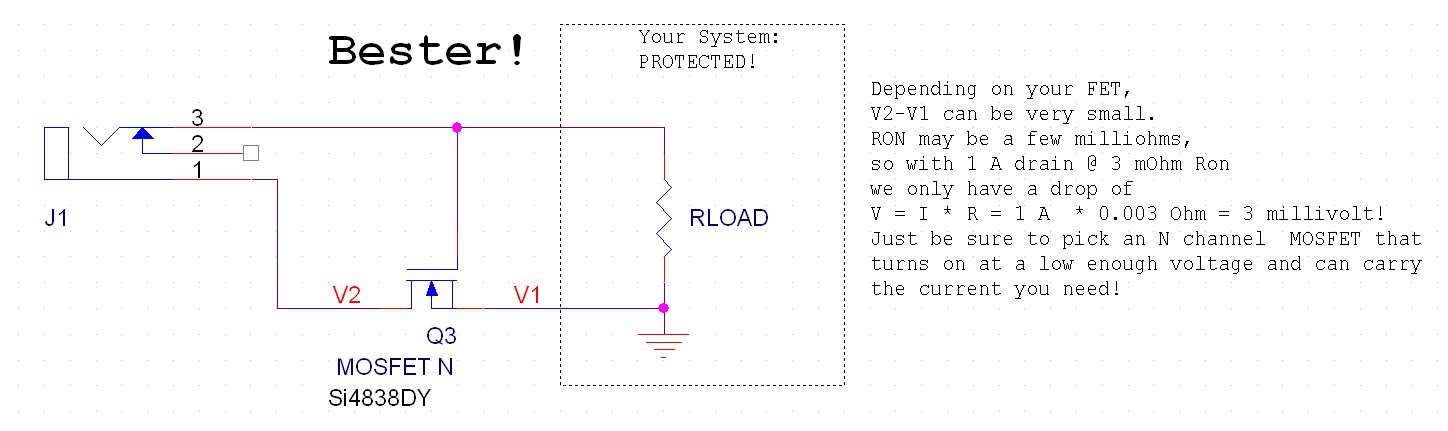

The third image shows a simple trick for reverse polarity protection that has a minimal voltage drop across the protection device. In this case, you use an N-channel MOSFET on the return (negative) side of your project.

When the DC voltage is connected properly, the MOSFET's gate is pulled high relative to its source, which turns it ON. In this case, the FET behaves like a low-value resistor. When the DC voltage is reversed, the gate is pulled LOW relative to its source, and the FET turns off. Simple as that. Mostly.

You must choose a MOSFET with a low enough turn on voltage that it's FULLY turned on at your minimum operating voltage, and has a low enough RDSon at your operating voltage that your voltage drop will be low enough for your system to operate. I show a Si4838DY that will fit the bill for many projects. At Vgs = 2.0V, it has an ON resistance of only 0.003 ohms! And it can handle up to 60 Amps, so it's effective for low and high current applications. It's expensive, at over $3.00 each though ($1.50 in quantity). For less demanding applications, perhaps a IRLML6344TRPBF will better fit the bill. It's only $0.50 ($0.13 in quantity).

As your operating voltage goes up, a whole plethora of transistors open up, that may be better suited for your application, and cheaper. Just be sure to look at the RDSon vs. Vgs chart on your proposed transistor. Once you learn to peruse the DigiKey search engine and scan the data sheets, you can find transistors pretty quickly.

By the way, carefully check to make sure that you don't reverse the Source and Drain of the transistor! If you do, the body diode of the FET will conduct during reverse polarity connection, and you'll fry your circuit.

Well, I have. It can ruin your day.

The easiest way to protect your system from a reversed battery is seen in the first image. Simply put a diode in one leg or the other of your circuit (usually the + side). If you don't care about your system's efficiency, and you have at least 0.7 V of margin when your DC supply is at its lowest possible value, then this will work fine. RLOAD represents whatever the heck you're running -- a microcontroller, a coffee warmer, whatever.

However, if you have less than 0.7V of margin in your system, you may replace the diode with a Schottky diode. This brings your drop down to 0.3V. Better, but still not great. For example, if you're running a system from 2 AA cells, you still can't afford the ~0.3V drop of a Schottky because you may have a chip that requires 2.0V to run, and NiMH cells bottom out at about 1.0V/cell.

So, what's a guy (or gal) to do?

The third image shows a simple trick for reverse polarity protection that has a minimal voltage drop across the protection device. In this case, you use an N-channel MOSFET on the return (negative) side of your project.

When the DC voltage is connected properly, the MOSFET's gate is pulled high relative to its source, which turns it ON. In this case, the FET behaves like a low-value resistor. When the DC voltage is reversed, the gate is pulled LOW relative to its source, and the FET turns off. Simple as that. Mostly.

You must choose a MOSFET with a low enough turn on voltage that it's FULLY turned on at your minimum operating voltage, and has a low enough RDSon at your operating voltage that your voltage drop will be low enough for your system to operate. I show a Si4838DY that will fit the bill for many projects. At Vgs = 2.0V, it has an ON resistance of only 0.003 ohms! And it can handle up to 60 Amps, so it's effective for low and high current applications. It's expensive, at over $3.00 each though ($1.50 in quantity). For less demanding applications, perhaps a IRLML6344TRPBF will better fit the bill. It's only $0.50 ($0.13 in quantity).

As your operating voltage goes up, a whole plethora of transistors open up, that may be better suited for your application, and cheaper. Just be sure to look at the RDSon vs. Vgs chart on your proposed transistor. Once you learn to peruse the DigiKey search engine and scan the data sheets, you can find transistors pretty quickly.

By the way, carefully check to make sure that you don't reverse the Source and Drain of the transistor! If you do, the body diode of the FET will conduct during reverse polarity connection, and you'll fry your circuit.